Back to Basics: Making Breastmilk

Breastfeeding is one of the most natural and beneficial ways to nurture your baby, but the process behind it is incredibly intricate. At Innovations Family Wellness, we often hear from mothers across Tulsa who want to know more about how their bodies make milk and how they can best support milk production. Taking a deep dive into the science of milk production, covering everything from the milk-making glands in your breasts to the powerful hormones that drive the process is important.

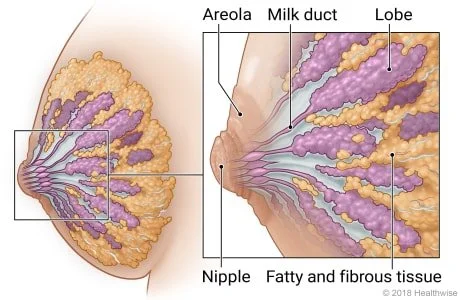

The Alveoli: Your Body's Milk-Making Glands

The starting point for milk production is the alveoli, small, grape-like structures located deep within the breast tissue. Each alveolus is surrounded by muscle cells that contract to release milk into the milk ducts when needed. These glands are responsible for creating milk in response to hormonal signals from your body.

The milk-making process starts during pregnancy. As your body prepares for your baby’s arrival, hormones such as estrogen and progesterone help develop the alveoli and the ducts that will carry milk. However, it's only after birth—when estrogen and progesterone levels decrease and prolactin increases—that the alveoli begin producing more milk.

The Letdown Reflex: A Key Player in Milk Flow

Once your baby is born and begins to breastfeed, the letdown reflex takes center stage. This reflex is crucial for releasing milk stored in the alveoli. It works by sending a message from the nerves in your breast to your brain. This message triggers the release of two key hormones—prolactin and oxytocin.

While prolactin is responsible for stimulating the alveoli to produce more milk, oxytocin causes the muscles around the alveoli to contract, pushing the milk into the ducts so it can flow to your baby. This process happens every time your baby nurses, ensuring a continuous supply of milk.

You might notice the letdown reflex as a tingling or warm sensation in your breasts when your milk begins to flow. It can also be triggered by other stimuli, such as hearing your baby cry, thinking about nursing, or during regular pumping sessions.

The Role of Hormones: Prolactin, Oxytocin, and More

Your body relies on a delicate balance of hormones to produce and release breast milk. Here’s a closer look at the key hormones involved:

Prolactin: This hormone is produced in the pituitary gland of your brain and is directly responsible for milk production. The more your baby suckles, the more prolactin is released, which stimulates the alveoli to produce more milk.

Oxytocin: Known as the "love hormone," oxytocin plays a dual role in breastfeeding. Not only does it help trigger the letdown reflex by contracting the muscle cells around the alveoli, but it also fosters bonding between you and your baby. This hormone is released in response to skin-to-skin contact, promoting relaxation and emotional connection.

Estrogen and Progesterone: During pregnancy, these hormones work together to prepare your breasts for lactation. Their levels drop sharply after birth, allowing prolactin to take over.

The Cycle of Milk Production: Supply and Demand

Breastfeeding operates on a “supply and demand” principle. The more frequently your baby nurses or the more you pump, the more milk your body will make. Each time your baby suckles, a signal is sent to your brain to release prolactin and produce more milk. This is why frequent feeding or pumping—especially in the early days after birth—helps establish a robust milk supply.

In the first few days postpartum, your body produces colostrum, a nutrient-rich, antibody-packed form of milk that helps protect your baby from infections. After a few days, your milk "comes in," and your body starts producing mature milk. The more often your baby empties the breast, the more efficiently your body replaces the milk, ensuring a continuous supply.

Factors That Affect Milk Supply

Every breastfeeding journey is unique, and while many mothers produce ample milk, some may struggle with supply. Several factors can influence your milk production:

Baby’s Latch: Ensuring your baby has a good latch is critical for effective milk transfer. A poor latch can lead to insufficient milk removal, which can signal your body to slow down milk production.

Frequency of Nursing: Nursing or pumping more frequently helps maintain a steady supply by encouraging prolactin production. Aim for 8-12 breastfeeding sessions per day in the early weeks.

Hydration and Nutrition: Staying well-hydrated and eating a balanced diet rich in nutrients can support optimal milk production. Nursing mothers should aim for an extra 300-500 calories per day to keep up with their body’s energy demands.

Breastfeeding Tips for a Healthy Milk Supply

Here are a few practical breastfeeding tips to ensure a healthy milk supply:

Nurse on Demand: Let your baby nurse whenever they show signs of hunger, especially in the early days. Frequent feeding helps establish your milk supply.

Offer Both Breasts: Alternate between both breasts during each feeding to stimulate milk production on both sides.

Practice Skin-to-Skin Contact: Skin-to-skin contact with your baby can stimulate oxytocin release, which helps with the letdown reflex and promotes bonding.

Stay Hydrated and Eat Well: Drinking plenty of fluids and maintaining a healthy diet rich in essential nutrients can support your body’s milk production.

Get Support: If you’re experiencing difficulties with breastfeeding, working with a Tulsa lactation consultant can provide valuable insights and personalized support. You can always call our office at 918-398-3586 or visit the contact page of our website.

Additional Resources for Learning About Milk Production

If you’re interested in learning more about how your body makes milk, check out these educational videos:

How does a woman's body produce milk? – This video explains the complex relationship between hormones and milk production.

Basics of Milk Production for Breast Feeding Mothers – A useful resource for breastfeeding basics.

How milk is produced in the mother's body (3D Animation) – A visual and detailed look at how milk is produced.

Breastfeeding is a beautiful journey, but it’s not always easy. Understanding the process and receiving the right support can make a world of difference. Our team of IBCLCs and RNs will be here to guide you every step of the way.

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, Volume 85, Issue 10, 1 October 2000, Pages 3661–3668, https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.85.10.6912